In the last few years, Kubernetes has grown exponentially in popularity. Its wide adoption can be attributed to its open-source nature, flexibility, and ability to run anywhere. Developers also love the fact that you can manage everything in Kubernetes using code.

kubectl is the Kubernetes-specific command line tool that lets you communicate and control Kubernetes clusters. Whether you’re creating, managing, or deleting resources on your Kubernetes platform, kubectl is an essential tool.

In this article, you’ll learn about kubectl, why it’s needed, what it can do, and how it works.

Your Kubernetes platform is a contained system with master and worker nodes. The only way to communicate with it is through its API server. This server is a core component of the Kubernetes control plane, and it exposes an HTTP REST API that enables the communication between users, the cluster, and all external components.

The API is considered the frontend or main user interface for your Kubernetes platform. Querying, updating, or managing the state of the resources or objects on your Kubernetes platform are all done with interactions using the Kubernetes API using kubectl, client libraries, or by making REST requests directly.

kubectl is the most common way to make HTTP requests to the Kubernetes API, and it’s used to run Kubernetes operations, deploy containerized applications, inspect and manage the resources in your cluster, as well as perform monitoring tasks and viewing the logs of the system.

Your kubectl commands will run on a command line connected to your installed Kubernetes on the cloud; for example, Google Cloud or locally.

kubectl commands follow a specific syntax with commands like get, delete, and config coming after the declaration (kubectl). Then the resource types being accessed (i.e. pods, deployments, or services) are followed by the name of the resource if needed (this is optional for the kubectl syntax). Flags modifying the entire command, showcasing location (-f), or port (–port), can be added as necessary.

The kubectl syntax utilizes this format:

For example, kubectl create namespace samplespace creates a namespace called samplespace and kubectl get pods -o wide generates a list of all pods with additional details about each pod. If you want to delete a specific pod named sample-pod-0, you can use kubectl delete pod sample-pod-0 to do so.

kubectl can be installed on your Linux, Mac, or Windows system using package installers or curl commands for the latest versions. Some Kubernetes-related software like Docker Desktop or minikube install kubectl on default, so it’s important to note which environment your kubectl command is pointed at or configured to. If you want to check this information, you can use kubectl config view. This command showcases your current Kubernetes configuration (kubeconfig) and the exact kubernetes environment your kubectl command will apply to.

If you’re looking to change the details of your kubernetes configuration, you can use commands like kubectl config set-context, kubectl config set-credentials, and kubectl config set-cluster to edit the parameters of your kubeconfig. This lets you easily switch the user, namespace, or cluster fields, allowing these parameters to be used by kubectl to communicate with your Kubernetes cluster.

If you wanted to install kubectl on Windows you can use Chocolatey, Scoop, or curl. For instance, if you wanted to use Chocolatey, you could run the command below on Command Prompt or Windows PowerShell:

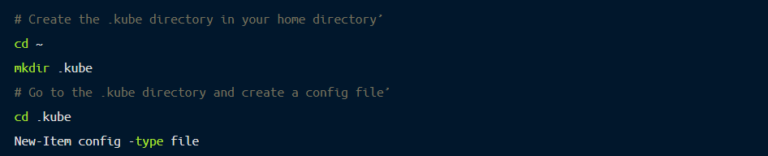

By default, kubectl requires access to the config file in your home directory under $HOME/.kube for authentication. This kubeconfig file contains authentication information including a user’s ID, password, or a secure token, as well as information about the deployed cluster(s). If you are installing it on Windows, you can create kubeconfig in your home directory using the following commands:

Configuration files are needed for cluster access in kubernetes. In addition, kubeconfig files and the context set for kubectl are critical to accessing multiple clusters from your command line using kubectl.

In a case where multiple clusters have been deployed on a system, for example, a system with Docker Desktop and minikube deployments running, you can use commands like kubectl config use-context to switch between defined configuration parameters.

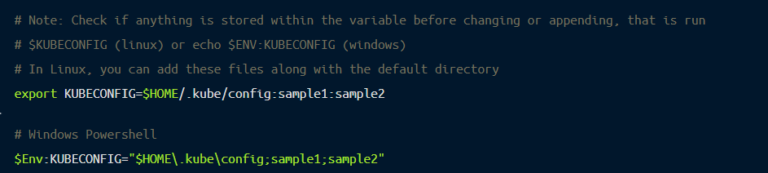

Additional kubeconfig files for other clusters can be added and merged into a single configuration file using the kubeconfig environment variable ($KUBECONFIG in Linux, $Env:KUBECONFIG, in Windows Powershell).

If you have multiple clusters with different rules for its users and namespaces, you can create different configuration files and merge them by appending their paths (the path to the config file) to the kubeconfig environment variable. This will then be given priority by kubectl as it points to the combined rules for all clusters.

For example, if you have two configuration files, named sample1 and sample2, it would look like this:

Commands using the –kubeconfig flag point to a specific configuration file, which will take precedence over the default $HOME.kubeconfig and the kubeconfig environment variable $Env:KUBECONFIG.

There are two common, valid methods of authenticating with kubectl in regular or production environments. These two methods are client certificates (Self-Signed Kubernetes Certs and Enterprise PKI Certs) and bearer tokens (service account tokens and OIDC tokens).

Under client certificates, based on industry standards, a valid x509 client certificate is needed. These certificates are validated and can be signed internally or externally.

Internally, the certificate is signed off by the cluster’s Kubernetes API server through a CertificateSigningRequest API call. This method can be easier and more convenient since it has no need for outside infrastructure, however, it’s unsuitable for large-scale deployments where requests are exponentially more and dedicated handling could be cost-prohibitive.

Externally, the certificate is signed by an external system administrator or an enterprise public key infrastructure (PKI).

There are multiple ways to authenticate using bearer tokens, but the easiest method involves creating a service account and generating a token from the account through the Kubernetes API. This token then authenticates any requests from that account, allowing access to the permitted clusters. This method is useful for long-term processes that continuously communicate with the Kubernetes API.

Another method for utilizing bearer tokens involves generating an external OpenID Connect (OIDC) token. This is well suited for user applications or enterprise purposes since it’s the most secure and scalable method for authentication. It’s helpful in large teams because it utilizes single sign-on tokens for all users of the clusters.

More information is available including specific code on the stated kubectl authentication methods.

Generally, kubectl can be used to perform or start up all Kubernetes operations. However, there are some commonly used functionalities for querying and managing the health of your Kubernetes cluster.

Listing and describing resources is one of these functionalities. As more resources are generated, you need to check on the state of these resources and to note the number of resources actively running at a point in time. This can be done using the kubectl get and kubectl describe commands.

Creating resources is another key way you can utilize kubectl. Through the use of the kubectl create command, you can create and schedule app deployments, services, cron jobs, and numerous other Kubernetes components or resources. With this command, and the flags available to it, you have granular control over the resources you want to create as well as where and when they are created.

Apart from creating Kubernetes objects, you can update and delete specific resource instances. If you created a resource using a file declaration (i.e. resource.yaml), you can utilize the kubectl apply command to update, refresh or reset the resource, depending on the changes in the file. You can also use kubectl edit to edit a specific resource instance (not the local file). This will bring up an editor where changes made will be updated in the resource. Finally, you can delete a resource using kubectl delete.

Debugging Kubernetes objects is made easy with the kubectl debug and kubectl logs commands. kubectl debug creates interactive debugging containers and kubectl logs prints out resource logs.

Finally, the ability to copy files and directories to and from containers is a helpful tool in working with Kubernetes through kubectl. The command you would implement to accomplish this is kubectl cp.

Kubernetes actively monitors the health of its objects, whether containers, deployments, or pods. The Kubernetes control panel reserves records of the configuration and state of all of the cluster’s Kubernetes objects while the controller manager observes the differences between the desired state and the actual state, and acts to rectify them.

Most objects in Kubernetes have a spec or specification and status. The spec is defined on the creation and declares the desired state for that object, while the status is a summary of the current state of the object.

Depending on the specific resource or object, you can observe its state using the kubectl get command, showcasing the resource’s status, and how ready it is (how far away from its desired state).

For example, pods have five values for its status (pending, running, succeeded, failed, and unknown) depending on the observed state of the pod.

When working in a team, debugging the state of your objects is crucial. Resources created by another user could limit the performance of your resources. In space-limited clusters, your created resource could be stuck on Pending, Waiting, or even fail because assets needed for its creation are currently in use. Use kubectl logs and kubectl debug to understand your object’s state and dig into possible reasons for failure.

kubectl is the main interaction most people have with Kubernetes, and there’s a lot it can do. It is extremely crucial in communication with the Kubernetes API and managing the Kubernetes clusters.

In this guide, you learned about what kubectl is and how it works. You saw how you can install, set up, and authenticate it. You also reviewed several use cases and commands that can help you get started with kubectl today.